105 Ways to Humiliate an American Company

Part 1: India, Korea, Japan — A Field Guide to Origins of Tariff Wars

A Tariff for a Tariff: India’s Game of Access Denied

Bourbon gets hit with a 150% tariff in India. Meanwhile, India sells to the U.S. at just 3.3%. That’s not a trade relationship — that’s a charity.

The United States often gets painted as the aggressor in global trade disputes, but when you look closer, American companies are routinely boxed in and disadvantaged in key foreign markets. One of the most glaring examples is India.

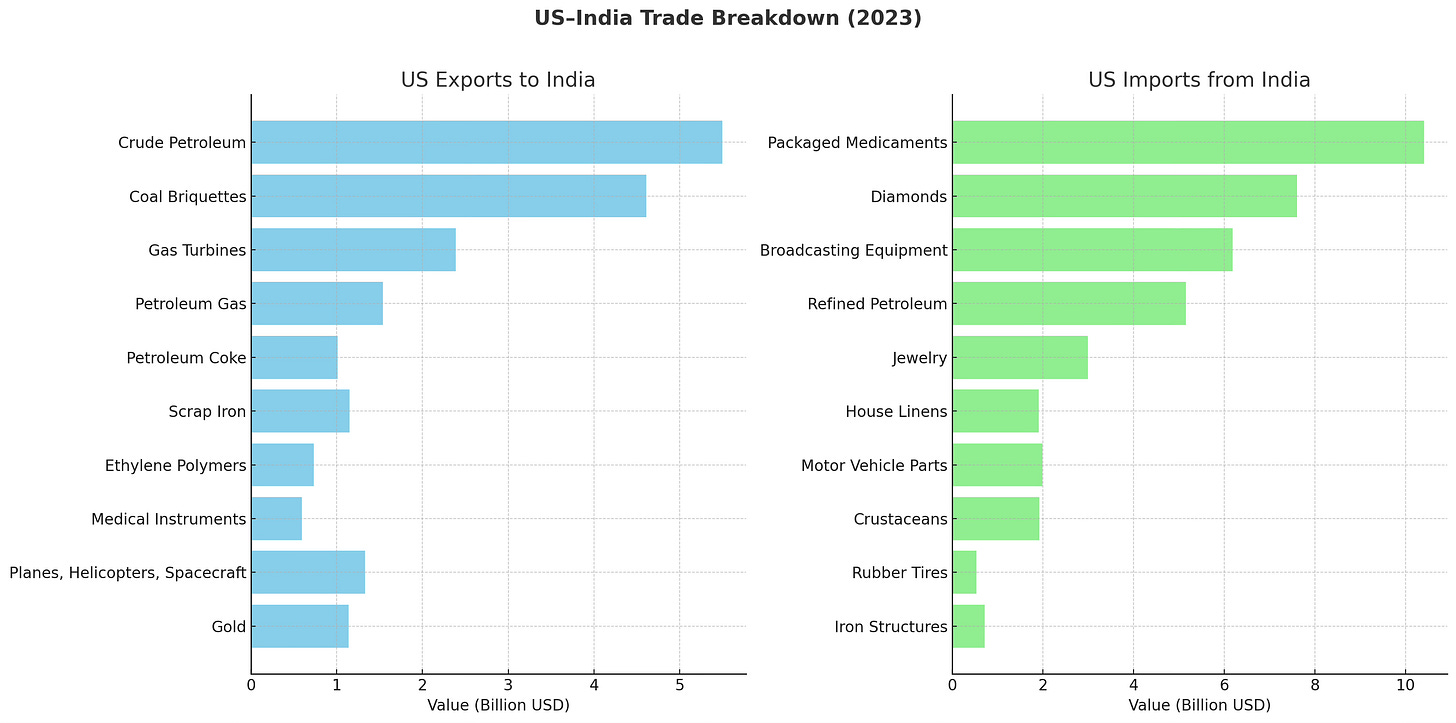

The average tariff on U.S. goods entering India stands at 17% — more than five times the 3.3% tariff India faces when exporting to the United States. The gap is even wider in agriculture, where U.S. goods are hit with a 39% tariff compared to just 4% on Indian exports.

It’s no surprise, then, that the U.S. runs a $45 billion trade deficit with India. Now, India is facing the threat of a 26% tariff from Washington — and appears willing to negotiate in order to avoid it. That’s what the press releases say. Reality looks different. American negotiators are demanding something real: genuine market access for U.S. retailers, defense contractors, and energy companies.

Amazon Can’t Sell, Reliance Can’t Lose

Let’s start with a simple example. Amazon and Walmart, two of America’s biggest retail giants, operate in India through local subsidiaries, but face heavy restrictions. They're barred from holding inventory or selling directly to consumers — essentially forced into being logistics providers for third-party sellers.

Meanwhile, India’s homegrown giant Reliance faces no such barriers. It not only operates physical stores across the country but also leverages its sprawling retail network to dominate every corner of the market. In effect, U.S. companies play by one rulebook — and Indian conglomerates by another.

Will JD Vance’s upcoming visit to India prove more successful than his stop at the Vatican? India now finds itself caught between two fires. On one hand, support from the United States is crucial in its never-ending rivalry with China. American companies are shifting production to India, and the country has a real opportunity to take China’s place in the global supply chain.

On the other hand, India continues to shelter its massive multi-sector conglomerates from meaningful Western competition. Reliance, for example, is active in oil, gas, textiles, and polymers — and its owner, Mukesh Ambani, resides in the most expensive home in the world, worth $4 billion. In a country where poverty is still widespread, this kind of display is more than just opulence — it’s a symbol of entrenched economic power.

Opening the gates would rattle the entire power structure Modi’s built his coalition on. The latest elections weren’t exactly a sweeping victory for the current government, and Prime Minister Modi now faces a difficult decision.

Adani, Ambani, and the Art of Domestic Control

Despite India's clear interest in maintaining ties with the U.S., its economic policy can hardly be called pro-Western. India remains focused on building massive multi-sector conglomerates that both support the ruling party and drive growth across everything from infrastructure to retail. One of the country’s top oligarchs, Gautam Adani, was accused of defrauding American investors and formally charged in November last year. In short, this won’t be an easy transition. India may need the U.S., but its policy of non-alignment — a holdover from the Cold War — is still very much alive. India will act on cold calculation, not ideology. Ironically, that’s exactly where it might find common ground with Trump.

Trade Alliance or Trade Trap? Inside South Korea’s Closed Doors

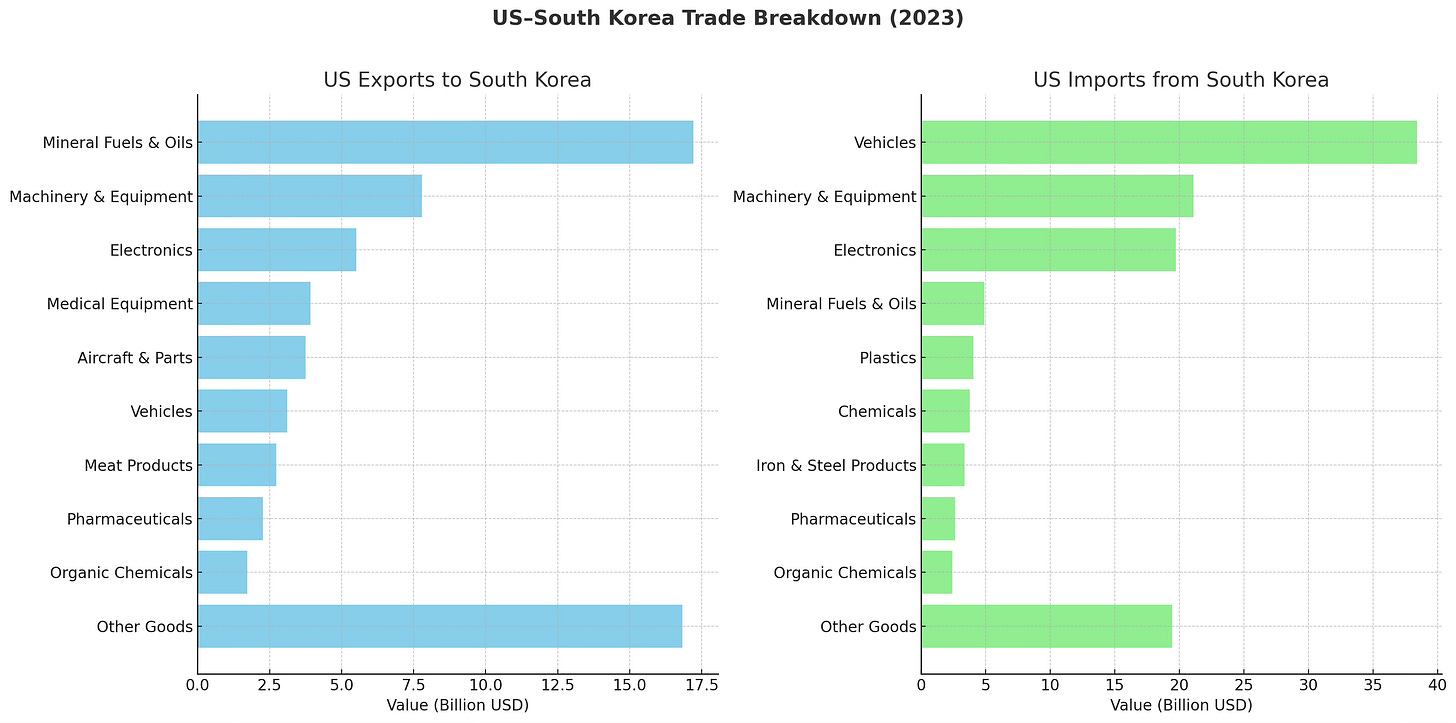

South Korea is a special case. Tariffs with the U.S. were effectively eliminated under the KORUS trade agreement, but the country has introduced an arsenal of non-tariff barriers that effectively close the door to many American companies.

While the average tariff rate on imports from the United States stood at just 0.79% as of 2024—and is expected to fall even further this year, with no duties on manufactured goods—the trade balance tells another story. The U.S. ran a $28 billion trade deficit with South Korea in 2023. Now, Washington is floating the possibility of a 25% tariff on Korean goods to restore some measure of balance. That threat has yet to provoke meaningful reform.

Coupang, Google, and Korea’s Quiet Clampdown

One of the most visible examples is South Korea’s Fair Trade Commission (KFTC), which has become a key driver of regulatory pressure targeting foreign firms. In 2023, KFTC fined U.S.-based Coupang approximately 140 billion KRW (roughly $98 million) for standard e-commerce practices like algorithm-based product placement. South Korean courts later suspended the fine — but the message was clear: play by a different set of rules, or pay the price.

Google and YouTube are also under constant scrutiny. Korea is pushing to impose "network usage fees" — effectively charging American tech firms for the traffic their platforms generate, even though Google’s infrastructure supports nearly 30% of the country’s internet backbone. Netflix has been targeted as well, with KFTC probing its cancellation policies and threatening further penalties.

Then there’s data — or the lack of access to it. South Korea continues to restrict the export of location-based services, including Google Maps, making it harder for U.S. companies to optimize global services. These measures act as de facto tariffs, placing selective burdens on American tech, while Chinese and domestic players scale up with far less friction.

This behavior is especially glaring given the broader context: the U.S. guarantees South Korea’s security with troops on the ground and a nuclear umbrella — yet American companies are often treated as intruders, not partners.

A recent report by the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF) underscores this point. ITIF is one of Washington’s most respected bipartisan think tanks, often referenced by both parties in Congress. Many credit the organization with informing Trump-era trade rhetoric, including the now-cited figure that 81% of vehicles sold in South Korea are produced domestically.

"American firms, especially in the tech sector, are increasingly facing steep compliance costs and legal uncertainty both in Korea and around the globe, while Chinese players like Temu and AliExpress — now exceeding 14 million monthly users in Korea — navigate global markets with comparative ease. This double standard doesn’t just undermine bilateral trust; it threatens South Korea’s long-term competitiveness in the digital economy", - writes ITIF.

Between Pyongyang and Palo Alto: What Korea Really Wants

South Korea and India share a lot in common. Both are relatively closed economies built around powerful multi-sector conglomerates — in Korea’s case, titans like Samsung and Hyundai. The U.S. hopes to challenge this structure, betting on deeper market access and regulatory reforms. There’s a good chance for that — because in order to deter North Korea, South Korea needs the U.S. military alliance more than ever.

Trump hasn’t yet said he plans to withdraw troops from the peninsula during a second term — but nothing can be ruled out. At the same time, America’s own presence in Korea isn’t just about Pyongyang — it’s a strategic springboard for keeping China in check.

The friction here isn’t just economic — it’s geopolitical. And in this environment, even modest market concessions might be bought not with trade agreements, but with fighter jets and troop deployments.

Polite Walls and Closed Markets: Japan’s Silent Strategy

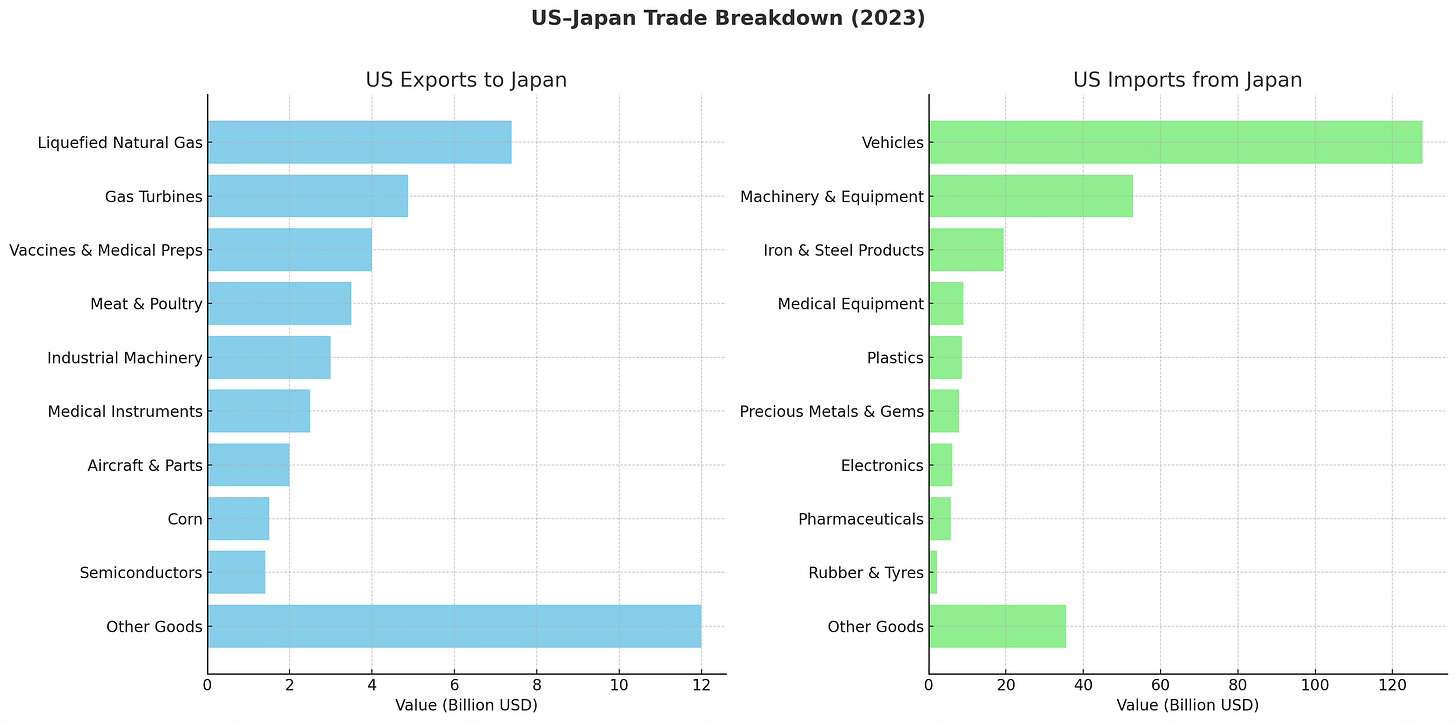

Japan sells even more local cars inside the country, than South Korea, 94%, that enraged Trump who slapped 24% tariff on the country with $63B trade surplus against US.

If South Korea tests the boundaries of alliance through regulatory pressure, Japan plays the game with subtlety — but the outcome for U.S. companies is often the same: limited access, preferential treatment for domestic giants, and entrenched protectionism dressed up in bureaucratic respectability.

Japan's average tariff on U.S. goods remains low due to a trade agreement signed in 2019, but non-tariff barriers continue to shape the landscape. Distribution channels are tightly controlled, domestic conglomerates dominate procurement networks, and foreign players often struggle to scale.

For example, U.S. pharmaceutical and medical device companies consistently report delays in product approvals compared to their Japanese counterparts. Meanwhile, the keiretsu system — networks of interlinked businesses with cross-shareholding — quietly reinforces domestic loyalty and limits outside competition.

Auto exports remain the elephant in the room. Japan exported over 1.6 million vehicles to the United States in 2023, while importing fewer than 20,000 in return. The imbalance is masked by Japanese automakers’ U.S. production facilities, but their headquarters — and profits — remain in Tokyo. What the U.S. sees as partnership, Japan has long treated as market acquisition.

In Tokyo, the White House often gets handshakes and summit photos, while American CEOs get stonewalled. There are exceptions: Toyota has firmly established itself inside the U.S. market, and SoftBank — through its Vision Fund — has invested tens of billions into American tech companies. Most recently, SoftBank participated in a $30 billion round for OpenAI, sparking a public feud with Elon Musk. Still, Masayoshi Son alone can't answer for Japan’s broader structural barriers. And yet, the U.S. continues to shoulder the burden of security in the region — through bases, alliances, and nuclear deterrence.

Domestic Loyalty

Japan’s position is even more layered. Economically advanced, tightly integrated with global supply chains, and home to some of the world’s biggest brands — yet still resistant to opening its domestic markets to true foreign competition. The keiretsu system may not grab headlines like China’s state planning or India’s industrial empires, but its effect is the same: it protects domestic giants and boxes out outsiders.

The U.S.–Japan security alliance remains one of the strongest in the world, but when it comes to trade, Japan still plays a cautious and self-serving game. Trump’s frustration with the country’s $63 billion trade surplus and its 94% domestic car production rate is not just political noise — it reflects a deeper imbalance.

Tokyo may not block American firms with the same blunt force as other nations, but the effect is similar: layered regulation, polite resistance, and market structures that reward domestic loyalty. The U.S. might be a partner in security — but in business, it's still often treated as a challenger.

And yet, like with India and South Korea, Trump could find Japan’s pragmatism strangely compatible with his own. If there’s leverage to be found — in bases, tech, or trade — expect him to use it

What’s Next

In Part 2, we head west — to the European Union and China. Two markets, two mentalities, but the same playbook: tariffs, red tape, and selective treatment of U.S. firms. If you thought India, Korea, and Japan were tough, just wait until we open the EU’s regulatory toolbox and China’s strategic state capitalism. Stay tuned.

This publication is for educational and informational purposes only and does not constitute financial, investment, or trading advice. Readers are solely responsible for their own investment decisions. The author may hold positions in the securities mentioned.